Hinne de Jong

A Chronicle

translated/arranged by his son, Sense de Jong

The "Fernando" shipwrecked

- 1: Introduction

- 2: Captain Pieter

- 3: Childhood years

- 4: Shipwreck

- 5: Teenager

- 6: Spring remembered

- 7: That's how it was

- 8: Pre World War I

- 9: Mobilization (1914-1918)

- 10: Boys will be boys

- 11: Hinne leaves Terschelling

- 12: Hinne meets his true love

- 13: An eventful move

- 14: A serious illness

- 15: The war years (1940-1945)

- A1: Memories of Pa (by Truus)

- A2: Memories of Moe (by Truus)

- A3: Pa talks again

- A4: Cornelis Jacob de Jong

Another site by Sense de Jong:

~ Sense de Jong ~

Reminiscences

Sites by Henry de Jong:

~ Herman de Jong ~

Memorial

~ Newmaker Notes~

Writings, Pictures, Collections

~ AACS/ICS Niagara Conferences~

1970 - 1991

Anyone familiar with the village of West Terschelling knows about a small, brick building that stands close to the harbor. It 's called “Het Wakende Oog," (Dutch = The Watchful Eye). The building itself is some sort of a waiting station. On the harbor-side, imbedded among the old bricks, you notice a stone sculpture depicting one large eye, with a painted, black pupil. On any day of the week, you might see the village elders - real old timers - sitting on a bench outside, leaning on their sticks and gazing out over the sea. Chewing their tobacco wads, spitting the occasional stream of tobacco juice on the pavement between people who happen to pass by, they gossip, reminisce and talk about the ships coming and going into the harbor. And they'd talk about the old days....

In bygone years this was the place where the villagers would gather during periods of stormy weather and high seas, especially when news was circulating that the famous Terschellinger lifeboat had been called to try to come to the rescue of a ship in trouble. After waiting many tense hours, they would cheer when the lifeboat returned safely to the harbor. And then they would learn what had happened on the stormy seas. Were they able to get the whole crew off the foundering ship? What happened to the ship? Did anyone of the Terschellinger lifeboat crew get hurt? A hush would come over the crowd when they saw the crew unload the bodies of those who had died, or those who had been hurt, sometimes badly. And then they would also learn that some were missing. Can you imagine the scene when the skipper of the lifeboat told them that one or more Terschellinger men were missing and had presumably drowned?

The de Jong farm was located just down the road from this little building. On a certain day, in November of the year 1908, Hinne was in school, in Grade Six. And he recorded how the principal, Mr. Wichers, entered the class shortly after 11 o'clock that morning to bring some shocking news.

Fall 1908 -Terschelling grieves

On November 24, 1908, the Italian three-master schooner “Fernando” ran aground in a flying storm on the dangerous shallows just north of Terschelling. The ship was loaded with timber from Riga and was bound for Swansea. It had a crew of 14.

At 0100 the ship was seen by the coastguard of Terschelling, from the top of the lighthouse "Brandaris." Because of the wild and furious seas, it was decided to wait until 0530 to start a rescue effort. The tugboat "Neptunus" was ordered to tow the Terschellinger lifeboat out to sea. There were 12 men on board the lifeboat: Klaas Knop (skipper), his son, Steven Knop, H. Former, J. Brouwer, A. Starrenburg, J. Gorter, Joe Brouwer, Teunis Brouwer, C. Wiegman, S. Wiegman, G. de Beer and Steven Wiegman.

Hinne wrote: "At 11 o'clock that morning the people (standing by 'Het Wakende Oog') saw the 'Neptunus' return to the harbor flying the flag in the half-mast position and no sign of the lifeboat. Soon the news spread that the lifeboat had completely turned over. A little later, our principal, Mr. Wichers, entered our classroom and told us what had happened . Some of the members of the lifeboat crew were the fathers or brothers of certain boys and girls in my class. You can imagine how deeply this affected us. Most of us were crying. When school was over we all ran to the harbor. Arriving at 'Het Wakende Oog,' we saw that people were busy resuscitating G. de Boer and Klaas Knop. They succeeded!"

Hinne explained what had happened: "Notwithstanding the high seas, Klaas Knop and the rowers managed to get closer to the 'Fernando' and come alongside. With great difficulty they managed to haul five men into the lifeboat. Only the 'Fernando' captain and a seaman remained on the wreck. The lifeboat could no longer stay in that position and it was decided to leave. A mighty ground swell caused the lifeboat to stand up straight in the water. Everybody on board fell into the sea. Ten men, i.e. the five who had been saved and five rowers managed to crawl back on the turned-over lifeboat. The others were floating some 15 meters away on their cork vests. High tide caused the lifeboat to drift away from the dangerous surf. The men on the 'Neptunus' saw what was happening and immediately lowered a flat-bottomed raft (Dutch=vlet). Eight men jumped in and started rowing towards the overturned lifeboat and picked up the ten men aboard. The tugboat 'Terschelling,' which had arrived at the scene, plowed through the surf and picked up five of those floating there. One of them, Heer Former, was dead. Klaas Knop and G. de Boer were injured and unconscious (they were revived - see above). Teunis Brouwer and Steven Knop were absent, never to be found. One of the two men left behind on the 'Fernando,' a sailor with a broken leg, was rescued by the Midslander lifeboat. The other person, the captain, apparently in a fit of madness, jumped overboard and drowned.

On this day, November 24, 1908, eight sailors and three, brave lifeboat rowers - well known to Hinne’s family - lost their lives. One of them – Steven Knop – was the son of the skipper.

So far, the "Fernando" story. Hinne’s memoirs show how deeply he was affected by this calamity. He deeply respected the bravery of the Terschellinger skipper and his eleven rowers who willingly went aboard the lifeboat and risked their lives for those in great need....

The rescue efforts of the brave Terschellingers became a well-known tale in Europe. Italy’s King Victor Emanuel III spoke about the “il corragio e la perseveranza” (i.e. the courage and perseverance) of those who braved the seas trying to rescue the men on the “Fernando.”

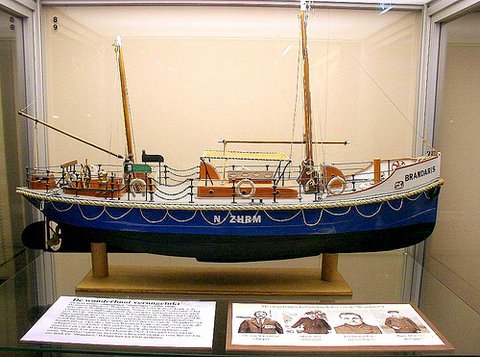

This rescue attempt also made the Terschellingers aware that there now was a great need for a a new, much more powerful, lifeboat. On November 8, 1910, the long-awaited new lifeboat arrived in the harbor. Its name was “Brandaris.” This vessel became the now legendary lifeboat associated with many subsequent rescue dramas around Terschelling.

The majestic view from the dunes along the North Sea

Postscript by Sense de Jong

How often have I not stood on the dunes of Terschelling gazing over the North Sea, imagining that somewhere in the distance the great swells of the Atlantic Ocean were beginning to roll to the very spot where I stood. The immensity and stillness of the vast beaches surrounding Terschelling always left a lasting impression on me. And always, you heard the sea, an unforgettable sound. The ever-shifting sandy shores of not only Terschelling, but of all the northern islands of the Netherlands, are extremely dangerous, even in the best of times. They are deadly when a “nor'wester” strikes. Many, many ships have come to grief here. The sandbanks of Terschelling have always been notorious and every lifeboat skipper from different ports knew about them.

The harbor of the village of West Terschelling lies on the opposite side of the North Sea. The sea between the mainland and the island – “Wadden Zee” - is often relatively calm, but it can be spooky there, too. In order for the Terschellinger lifeboat to get to the open seas, it immediately has to turn right outside the harbor into the “Wadden Zee.” It then follows a series of buoys which indicate where the "Noordvaarder" (an immense, flat sandy area, which starts by the village and ends by the dunes of the North Sea ) boundaries are. In a big storm, with high tides, even the "Noordvaarder" (today several square kilometers in size) is under water! Following the buoys, the lifeboat skipper then steers his boat towards the "Stortemelk," that area of the sea which lies between the islands of Vlieland and Terschelling. It is one of the most dangerous spots in all of Holland, I think. In stormy weather, with shifting tides, the current there is so strong that it requires a superhuman effort to get through it. I've read stories that, in these narrows, the sea in a big storm is like a cauldron, with waves as high as two stories. Many lives have been lost here....

Above, the legendary lifeboat "Brandaris" of yesteryear, and, below, one of the modern, unsinkable lifeboats of today.

The super-modern, unsinkable, powerfully- motorized lifeboats of today cut through this stuff like butter. They drive on and on, mostly under water. But I have seen pictures of the Terschellinger lifeboat of old, a sloop with six rowers on each side, each sailor clad in oilskins from top to bottom. All are wearing those sensible sou'wester hats. All have a pipe full of tobacco nearby. Strong, mighty men, with hands like shovels. And it is that picture that comes to mind when I read my Dad's account of the attempt to rescue the crew of the "Fernando" in the year 1908. I can just see that small band of people trying to get through the hell of the "Stortemelk," finally making it to the swell of the towering waves of the North Sea. Once there, the skipper steered them along the immense breakers of the surf towards a spot - which might be easily twenty kilometers away - where, he was told, a ship had come to grief. (Later, more lifeboat stations were built along the beach of Terschelling to cut down on that distance.) And then, the rescue effort itself. As always, having arrived at the ship, the men, bone-tired after such a trip, called upon even more strength, because there were lives to be saved. And, after everything was done that could be done, the hazardous journey back to the harbor began. - sdj

[an error occurred while processing this directive]