Sense's Reminiscences

by Sense de Jong

– Soli Deo Gloria

- Geurt

- Tante Betje (by Sense)

- Tante Betje (by Truus)

- Miss Roozendaal

- Concert in Winschoten

- A baptism remembered

- My birdhouse

- War veterans

- Henk Smit - bass/baritone

- Stefan

- In memory of Herman - I

- In memory of Herman -II

- Remembering AK

- Our love for music

- Herman - Promoter of Christian Causes

- A Salem evening with Herman de Jong

- From Elsinore to Monschau

- A Danish Treat

- Glimpses of Thuringia and Saxony

- Domie and Hansie

- La Manche, Newfoundland

- Bermuda - Isle in the Sun

- 1932 and 1934

- 1940 - 1945

- Winschoten, Grace on the Venne

- 1948

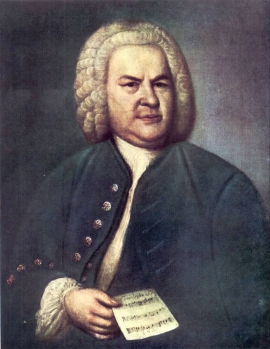

- Johann Sebastian Bach

- From Generation to Generation

- Seven children and a harmonium

- K.P. - A Man of Enterprise

- Cuba and the tragedy of the MS St Louis

- It all began in Norwich, Ontario

Another site by Sense de Jong:

~ Hinne de Jong ~

A Chronicle

Sites by Henry de Jong:

~ Herman de Jong ~

Memorial

~ Newmaker Notes~

Writings, Pictures, Collections

~ AACS/ICS Niagara Conferences~

1970 - 1991

"The aim and final end of all music should be none other than the glory of God and the

refreshment of the soul" – www.thinkexist.com (famous Johann Sebastian Bach quotes)

Some important dates:

1517 – Martin Luther (1483-1546) unleashes the Protestant Reformation when he nails his ninety-five theses to the church door in Wittenberg, Germany. Luther is born in Eisleben, Saxony, and studies in Eisenach as a youth.

1685 – Johann Sebastian Bach is born in Eisenach, Germany. He dies in 1750.

1685 - George Frideric Handel is born in Halle, Germany. He dies in 1759.

It’s an amazing fact that Bach and Handel, even though they were born in the same year and so close to each other, never met. It is true that Handel spent the better part of his life in England. In 1750, writes John Eliot Gardiner (see end notes below), Handel sets off for the continent for the last time and is injured in a coach accident between The Hague and Haarlem, delaying his arrival in his home town of Halle until a few weeks after Bach’s death, and so the two men never meet.

Both men were heavily influenced by the Lutheran faith and came from fine Christian homes. Bach dedicated all his compositions to God’s glory. The front page of each new work was always marked Soli Deo Gloria (to the glory of God alone). Handel also signed his oratorio manuscripts "S.D.G.G.F.H. (Soli Deo Gloria George Frideric Handel), according to Marian Van Til (see end notes below). Gardiner states: "The dedication of (Bach’s) art to God’s glory was not confined to signing off his church cantatas with the acronym S(oli) D(eo) G(loria; the motto applied with equal force to his concertos, partitas and instrumental suites. And Eisenach, his birth place and the site of his first encounter with Martin Luther, the founder of his inherited version of Christianity, is clearly a good place to start. "

Now it is true, I already wrote an earlier piece for this site ("Our love for Music" see above) which records the deep attachment I and my brother Herman had for the music of Bach, particularly for his masterpiece, the Matthew Passion. However, I guess there is more….

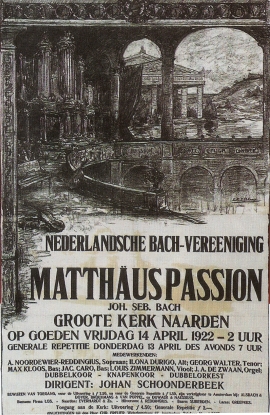

The Matthew Passion – Then and Now

During the 1940s many people (in the Netherlands anyway) considered the pre-war performance of the Matthäus by Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw Orchestra under the baton of Willem Mengelberg one of the outstanding performances at that time. On a sad note, famous as he was, Dr. Mengelberg’s name sank into disrepute because of his associations with the Nazis. During WWII (he was photographed in the company of the notorious Reichskommissar Arthur Seyss-Inquart!). In 1945 he was removed from his post as conductor of the Concertgebouw. He moved to Zurich, Switzerland, where he died in 1951.

In any event, we grew up often listening to the "Mengelberg version" of the Matthäus. Today, one could not imagine Holland without annual performances of Bach’s greatest work. The first performance took place in 1870 in Rotterdam and the next four years later in Amsterdam. On April 8, 1889, Willem Mengelberg conducted a shorter version of the Matthäus with a large orchestra and a choir of no less than 450 (!) persons. The Bach Society of the Netherlands started the tradition of an annual performance on April 14, 1922, in the Grote Kerk in the medieval fortified town of Naarden, located close to Amsterdam. My brother and I listened annually to the live radio broadcasts from Naarden in the 1940s. These performances were always conducted by Dr. Anthon van der Horst. I recently learned that each year the Matthäus is performed in more than 100 locations throughout Holland, the concerts taking place each Easter in either large concert halls or in one of the many stately churches in the country. Can you imagine the immense amount of rehearsals and preparations by many choirs and orchestras as well as soloists required to stage these events?

Today, those of us who are computer-savvy, can listen at any time to and view performances of the Matthäus directed by such celebrated conductors as Helmuth Rilling, Philippe Herreweghe, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Jos van Veldhoven, Peter Dijkstra, Frans Brüggen, John Eliot Gardiner, Ton Koopman, to name a few.

Going back in history, we learn that as far as is known, Bach himself conducted the Matthäus on April 15, 1729, in the Thomaskirche in Leizig. (He may have conducted an earlier performance on April 11, 1727, during the vesper service on Good Friday.) There is evidence that the work was also performed in 1736 and 1740.

After Bach’s death in 1750, however, the Matthäus and much of his other music sank into oblivion. But now enters that wonderful man, named Felix Mendelssohn, himself a famous composer of some repute. He decided to revive the Matthäus in Berlin in 1829 and again in 1841. On March 11, 1829, the Passion was heard again for the first time in 100 years! This performance marked the rediscovery of Bach as a composer, and a revival of his works began. (www.takte-online.de)

*******

Maarten ‘t Hart, a controversial Dutch author but a great Bach lover (see end notes), recorded part of an interview, as follows:

Interviewer: Do you agree that the Matthew Passion is the greatest work in music history?

Pablo Casals (famous cello player): I agree totally, a thousand times over.

‘t Hart, an organist, also praised Bach’s compositions for organ. Bach himself was a famous organist in his days and he left a legacy of many chorale preludes for organ, his trio sonatas for organ and many major organ works. ‘t Hart wrote: "If Bach had composed only his six trio sonatas, than that would already show his status as the greatest organ composer!"

*******

Praise God that after all those years Bach’s Matthew Passion continues to touch so many hearts today. It just thrills me to meet people all over whose eyes lighten up when the Matthäus is discussed or heard. Years ago, one summer around 1950 , when we were still teenagers, we decided to make a bike tour from the northern Dutch province of Groningen to the Veluwe, a beautiful nature reserve in the middle of Holland where you find marshlands, forests, vast fields of heather and sand dunes. It’s a considerable distance and I don’t remember how long it took us to get to our vacation resort close to Apeldoorn. Once settled in, I started roaming the premises. Lo and behold, I found a grand piano in one of the halls. Those things always have a magnetic attraction for me. I guess it’s because I always wanted to be a trained pianist or organist. It never happened. All I accomplished was teaching myself, on a pedal-pumped harmonium at home, to imitate some tunes from either a Bach toccata or oratorio, or something like that. So, I sat down at that piano and softly began playing – in my way – the opening chords of the Matthew Passion. After a while, an amazing thing happened. There were people standing around listening to my miserable attempt to do justice to this monumental opening movement that, as one writer wrote, "sets the dramatic, emotional, and theological tone for the entire Passion." I then overheard one mother say to her husband and children: "Luister es! Dat is de Matthäus." (Listen up! That is the Matthew Passion.) I will never forget that moment. I quickly explained that I was a hopeless musician, couldn’t read a page of music if my life depended on it, and with a red-face closed the lid of the piano. But that triggered off a very fine discussion with those people about how Bach’s masterpiece had impacted all of us. Today, I have no doubt that there are millions around the world who will always love, and be blessed by, the music of Bach and would agree, as one Toronto newspaper headlined, "Why his music can still turn any room into a church."

All my life, ever since hearing the Matthäus on Dutch radio during the 1940s, I would often perform in my head whole sections of the Passion, particularly the bass and tenor arias. Many times, while waiting for sleep, I would listen to the entire opening chorus and then would sang along with the incredibly moving aria "Erbarme dich" (Have mercy) scored for alto soloist, strings, cello and organ. How blessed I was when, during the early 2000s, as a second bass with the Robert Cooper-directed "Chorus Niagara", I had the privilege to participate in performances of the Matthäus, and later, the Hohe Messe (Mass in B Minor), in St. Catharines, Ontario.

Why is the opening movement of the Matthäus so memorable and deeply moving? The narrative text of the Passion is from Matthew’s gospel. The hymn texts were written by many different authors. The rest were written by Bach’s most frequent textual collaborator, the Leipzig poet C.F. Henrici, whose pen name was Picander. The foregoing is based on comments by music professor Ruth van Baak Griffioen which were included in the booklet produced for the April 11, 2003, performance of Bach’s Matthew Passion by the Bach Collegium Japan at Calvin College, Grand Rapids, Michigan, in connection with the conference "Bach the Preacher." This memorable concert was conducted by none other than Masaaki Suzuki, an internationally renowned Bach specialist. (He was awarded the prestigious Bach Medal 2012 by the German city of Leipzig.)

The opening movement calls for two choirs, soprano chorale line and two orchestras. The Picander-written text begins with the words "Kommt, ihr Töchter, helft mir klagen" (Come, you daughters, help me lament) followed by the chorale line "O Lamm Gott, unschuldig, Allzeit erfunden geduldig, All Sünd hast du getragen, Erbarm dich unser, o Jesu!" (O innocent Lamb of God, Always found patient, All sin you have carried, Have mercy on us, Jesus.) Ruth van Baak Griffioen writes: "A tremendous scene unfolds before us, with two choirs calling out questions and answers to each other as if across the very road Jesus trudges to his crucifixion. The figure in the road is revealed to be the Lamb of God and the Bridegroom of the Church in a vast vision stretching from the Old Testament to the New Jerusalem."

Bach and Luther in Eisenach

Following the nailing in 1517 of the ninety five these in Wittenberg, Pope Leo X excommunicated Luther. He was ordered to appear before the Diet of Worms (a town on the Rhine). Luther, however, had a secret benefactor. On one of the trips back to Wittenberg, Prince Frederik III, Elector of Saxony, had his masked horsemen intercept Luther and caused him to disappear to the Wartburg Castle in Eisenach, the same place where he and Bach received their early religious education, attending the same church, the Georgenkirche. (You may recall from an earlier article that my wife, Corrie, and I visited Eisenach in 2008. We saw the very place where Luther was hidden. Wandering through the town we visited the Bachhaus as well as the market square, the location of the beautiful Georgenkirche – see previous story "Glimpses of Thuringia and Saxony.)

John Eliot Gardiner once led a "Bach cantata pilgrimage" through Germany and this group stopped at Eisenach during the Easter weekend of 2000. The pastor at Eisenach welcomed them warmly. Writes Gardiner of this visit: "Eisenach, the pastor insisted, is the place where ‘Bach meets Luther’. Both Luther and Bach had once stood as boy choristers exactly where we were now standing as honoured guests invited to lead the singing of the Hauptgottesdients, or main service, on Easter Sunday 2000. From our position in the choir loft high up at the back of the late Gothic Georgenkirche, arranged like a three-decker galleon, we had an unimpeded view of the two most prominent physical symbols: the pulpit in which Martin Luther preached on his return from Worms in 1521 and the baptismal font where Bach was christened on 23 March 1685."

When in the hour of utmost need

The celebrated Canadian pianist Angela Hewitt recently recorded (for Hyperion) Bach’s monumental late work, the Art of the Fugue. It consists of 18 fugues and canons, which Hewitt describes as "completely overwhelming, both intellectually and emotionally."

Pamela Margles published a vey positive review of this project in the Dec. 2014 – Feb. 2015 issue of The Whole Note, a widely-distributed music magazine in the Greater Toronto area. I should mention here that on his deathbed – he died 28 July 1750 – Bach dictated to his second son, Carl Philipp Emmanuel, a chorale prelude based on the hymn Wen wir in höchsten Nöten sein (When in the hour of utmost need) - a tune by Louis Bourgeois, dated 1547.

The above review by Pamela Margles ends as follows: "Bach’s score ends, enigmatically, part way through the final fugue. Most performances stop there, or add on a completion in Bach’s style. Following the original edition, Hewitt stops mid-fugue, pauses, then plays Bach’s ‘deathbed’ chorale prelude Wenn wir in höchsten Nöten sein (When in the hour of utmost need), which C.P.E. Bach copied into the score after his father’s death. It makes for an intimate and moving finale."

Here’s a translation of the first stanza of this hymn:

When in the hour of utmost need

We know not where to look for aid,

When days and nights of anxious thought

Nor help nor counsel yet have brought,

Then this our comfort is alone;

That we may meet before Thy throne,

And cry, O faithful God, to Thee,

For rescue from our misery.

Johann Sebastian Bach – a man of faith, trusting in his God till the end.

S.D.G. – Soli Deo Gloria. To God alone the glory!

End notes

1) Recently, I rejoiced when I heard of the publication of a book by the famous English conductor John Eliot Gardiner, entitled "Music in the Castle of Heaven – A Portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach" (London, U.K.,Penguin Books, 2013), a most significant addition to my small music library. Having struggled through this 625-page tome (generally familiarizing myself with its content) I learned a tremendous amount from Gardiner’s great insights. As one reviewer put it, "This book is going to be as indispensible to Bach scholars as it is to general readers."

2) Another valuable addition is a most important book by Handel-expert Marian Van Til,

George Frideric Handel – A Music Lover’s Guide. Youngstown, NY: Word Publishing,

2007.

3) An interesting read, in the Dutch language, is Maarten ‘t Hart’s book Johann Sebastian Bach. Amsterdam, the Neth. Uitgeverij De Arbeiderspers, 2000.

St. Catharines, Ont.

May 2015

[an error occurred while processing this directive]